PORTLAND, Ore. — Portland Public Schools (PPS), Oregon’s largest district, is facing a federal lawsuit challenging its long-standing practice of distributing teachers and funding partly based on school demographics. The legal challenge marks a new front in the national debate over race-conscious policies in education.

Lawsuit Targets Equity-Based Funding Formula

The lawsuit, filed in U.S. District Court in Portland by the Center for Individual Rights, a Washington, D.C.-based law firm known for opposing race-based preferences, alleges that PPS’s staffing and budgeting system violates the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause and the U.S. Civil Rights Act.

The suit, first reported by Willamette Week, was brought by Glencoe Elementary parent Richard Raseley, who claims the district’s approach unfairly prioritizes certain racial and ethnic groups over others. Former Republican state representative Julie Parrish is among the attorneys representing him.

Also Read

At the center of the dispute is a PPS policy, in place since 2013, that gives 2% more funding — and the additional staff that money can support — to elementary and K-8 schools serving higher concentrations of students from historically marginalized groups. These include Black, Latino, Pacific Islander, and Native American students, as well as students in special education and English language learners.

High schools also receive “equity funding,” though theirs is based solely on the percentage of students whose families qualify for government assistance programs such as food stamps or Medicaid.

How the Formula Works

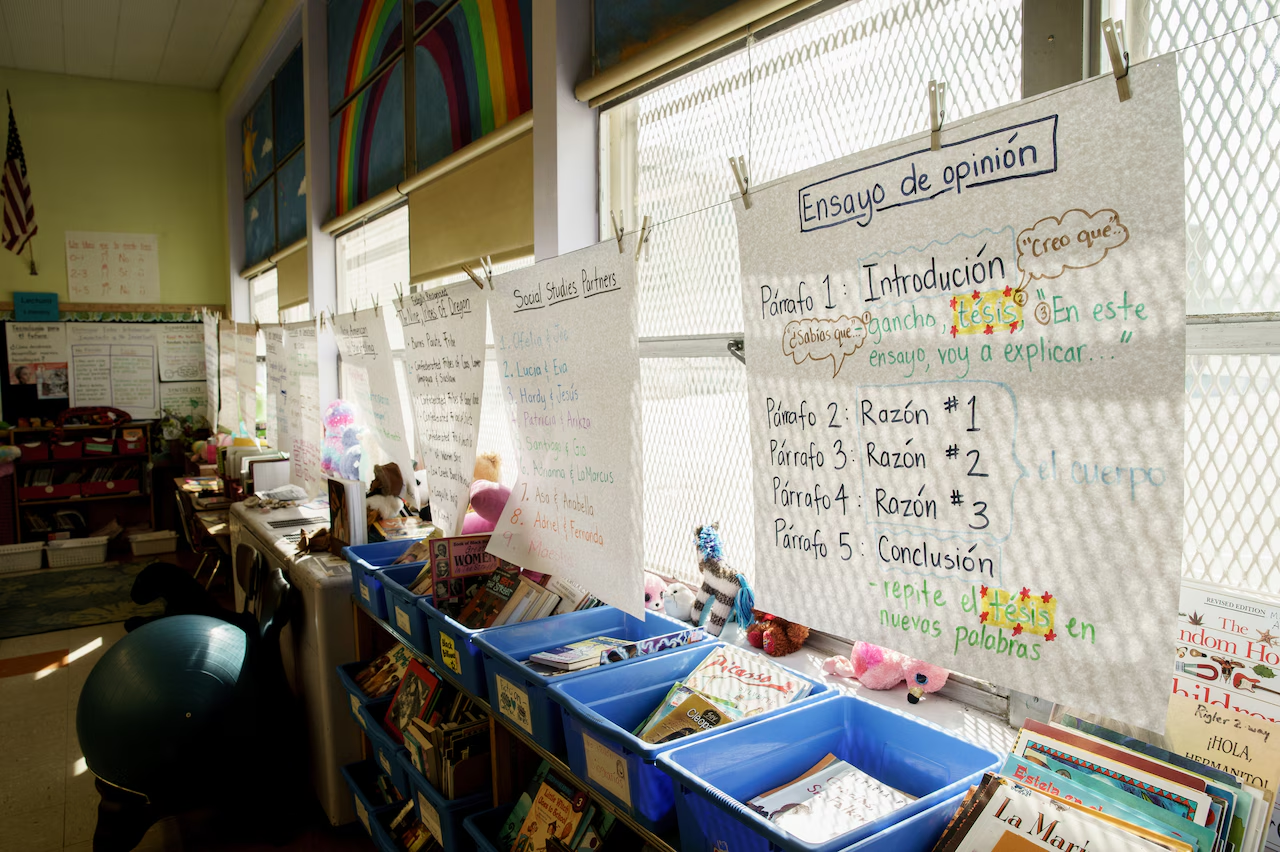

Under the formula, schools serving more students from disadvantaged backgrounds receive more funding for teaching and support staff. The policy was designed to narrow long-standing academic disparities and address barriers facing students who have historically had fewer resources.

In practice, the system has led to more teachers and specialists being placed at schools with higher proportions of non-white students or students from low-income families. These schools often serve communities where parents are less able to afford private tutoring or volunteer regularly in classrooms.

A Shifting Legal Landscape

For decades, many school districts across the U.S. used race and other demographics to guide resource distribution, acknowledging persistent achievement gaps between white and Asian students and their Black and Latino peers.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 decision striking down affirmative action in college admissions has reshaped the legal terrain. That ruling, along with the Trump administration’s opposition to race-based policies, has emboldened new challenges against programs seeking to redress racial inequities in education.

The PPS case is among the latest efforts by conservative legal groups to roll back what they view as unconstitutional racial preferences in public institutions. The Center for Individual Rights, which filed the Portland lawsuit, has previously supported similar litigation against universities and school systems nationwide.

Debate Over Fairness and Equity

Supporters of the PPS model argue that the formula is not about racial favoritism but about addressing real differences in opportunity. They note that students from marginalized communities often start school at a disadvantage due to systemic inequities — something the policy aims to mitigate through smaller class sizes, extra academic support, and more diverse staff.

Critics, however, say the policy crosses a constitutional line by linking funding decisions to students’ race. “Equity should not come at the expense of equal treatment under the law,” said one parent familiar with the case.

Dispute Over School Fundraising Policies

The lawsuit also challenges a 2023 decision by the Portland school board to end a previous fundraising policy that allowed individual school foundations — often led by parents — to raise private money to fund extra staff at their own schools.

Under the old system, schools could keep two-thirds of all funds raised above $10,000, with the remainder going into a shared district fund for redistribution to lower-income schools. Wealthier, predominantly white schools often raised tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars, while schools in poorer neighborhoods received far less.

To promote greater equity, the board voted to replace the model with a single districtwide foundation that pools donations for all schools. While equity advocates praised the move, others — particularly parents at high-income schools — criticized it as punishing successful fundraisers.

The financial impact has been significant. The districtwide foundation raised about $600,000 in its first year, a steep drop from the $2 million to $4 million generated annually under the previous system.

Broader Implications for Oregon and Beyond

The outcome of the lawsuit could have far-reaching implications, not just for Portland but for other districts nationwide that use demographic data to guide resource distribution. A ruling against PPS could force school systems to rethink equity-based budgeting practices that have become increasingly common in recent years.

Education experts warn that eliminating such policies could widen existing disparities. “Equity funding ensures that resources go where they’re needed most,” said one Portland educator. “Without it, the gap between high-income and low-income schools will only grow.”

As the case moves forward, PPS officials have not yet publicly commented on the lawsuit. Meanwhile, parents and educators across Portland remain divided — some viewing the challenge as a necessary defense of fairness, others as a direct attack on decades of progress toward educational equality.