OREGON — From rising temperatures to shrinking snowpacks, Oregon’s climate is shifting in ways that will reshape forests, rivers, and communities for decades to come. The Seventh Oregon Climate Assessment, published by the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute, offers a clear picture: climate change is no longer a distant threat, but a present and accelerating reality.

What We Know So Far

Measurements dating back to the late 1800s show Oregon has already warmed by about 2.2°F per century. Both maximum daytime highs and overnight minimums have climbed. Over the past two decades, droughts have become more frequent and severe, fueled by both lower precipitation and higher heat.

Snow is falling less often in the mountains, replaced by rain that runs off quickly instead of slowly melting to recharge rivers. Together, these shifts are placing new stress on forests, agriculture, and urban water systems.

What’s Ahead: Projections to 2100

Looking forward 50–75 years, scientists project continued warming across Oregon under all emissions scenarios. By 2044, average annual temperatures are expected to rise by 2.6–3.0°F, climbing to 4.6–5.9°F by 2074 and up to 9.1°F by 2100 in high-emissions models.

Precipitation overall may increase slightly in winter but decline in summer. A larger share of winter storms will be stronger, and more precipitation will fall as rain rather than snow. By midcentury, snowfall is expected to decrease by at least 50% across all major ecosystems.

Summer drought risk will rise statewide, with particularly sharp increases along the western slopes of the Cascades and in the southern Coast Range.

Key Climate Stressors

1. Extreme Heat

-

Ecological impacts: Water stress for sensitive tree species, shifting habitats, and surges in pests like bark beetles.

-

Social impacts: Greater risk of heat-related illness, strain on outdoor workers, and rising demand for air conditioning.

2. Snow-to-Rain Transition

-

Ecological impacts: Loss of natural water storage in mountain snowpack, reduced cold-water fish habitat.

-

Social impacts: Less water for irrigation and hydropower, and changes in the viability of winter recreation industries.

3. More Intense Drought

-

Ecological impacts: Higher tree mortality, stress on Douglas-fir, cedar, and other moisture-sensitive species.

-

Social impacts: Reduced water supplies for cities, farms, and households.

4. Wildfire Frequency and Scale

-

Ecological impacts: Increased tree mortality, regeneration challenges, and shifts from forest to shrubland.

-

Social impacts: Timber loss, poor air quality from smoke, displacement of residents, and higher firefighting costs.

Oregon’s Warming Trend

Since 1901, 21 of the past 24 water years have been warmer than average. Both daytime highs and nighttime lows continue to trend upward. This warming accelerates evapotranspiration—the process by which water evaporates and transpires through plants—leading to drier soils and stressed trees.

Combined with below-average precipitation in 18 of the past 24 years, this warming is turning even “normal” years into drought years, pushing ecosystems past their limits.

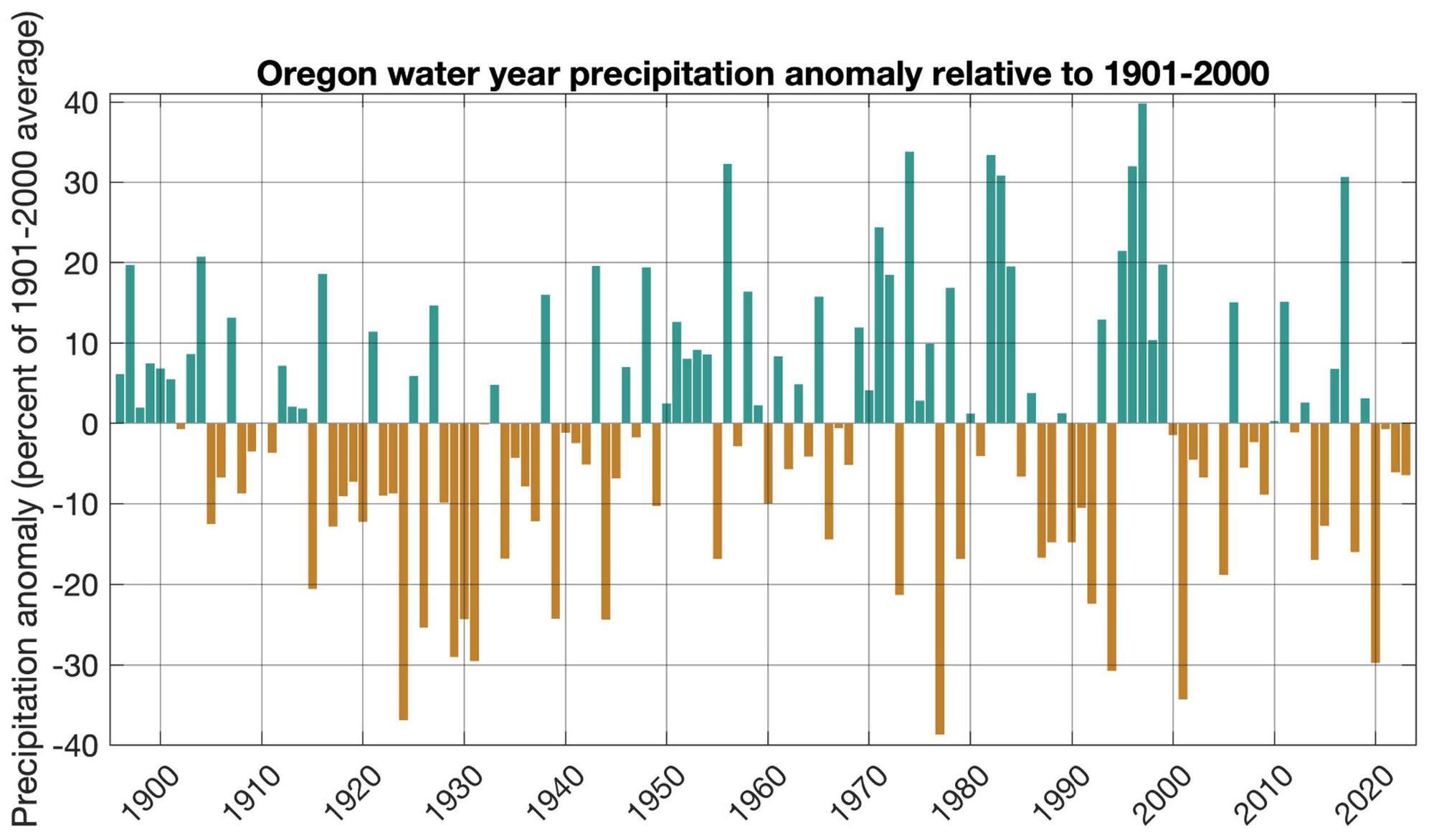

Precipitation Patterns and Drought History

While Oregon’s long-term precipitation totals appear relatively stable, the timing and form of precipitation are changing. Historical records show long droughts in the 1920s–30s and late 1980s–90s. Today’s droughts, however, are amplified by higher heat and the loss of snowpack.

Future projections suggest slightly wetter winters but drier summers. Southeastern Oregon could see as much as a 30–50% increase in rainfall replacing snowfall, while western Oregon may see a 3–10% shift. These changes will amplify summer water shortages even if annual totals remain steady.

Implications for Forests

The health of Oregon’s forests will depend on local conditions and tree species.

-

Douglas-fir: On warm, dry slopes or shallow soils, growth may decline sharply, with rising pockets of mortality.

-

Western hemlock and redcedar: Both are highly sensitive to reduced moisture and rising temperatures.

-

Resilient species: Forest managers may need to favor species or genotypes better adapted to drought and heat when replanting.

In practice, that could mean lower planting densities, shifting species mixes, or even reducing reliance on Douglas-fir in certain landscapes.

Social and Economic Dimensions

Climate impacts will ripple far beyond forests.

-

Water supplies: Declining snowpack threatens irrigation, hydropower, and domestic water storage.

-

Public health: Heat waves will raise risks of illness and mortality, particularly for vulnerable groups and outdoor workers.

-

Recreation: Ski resorts and snow sports will struggle, while hotter summers may reduce comfort and safety for hikers, campers, and hunters.

-

Timber industry: Increased wildfire losses and shifting tree viability may undermine one of Oregon’s cornerstone economies.

What Forest Owners Can Do

Because trees are long-lived, management decisions today will shape forest resilience decades into the future. Experts recommend:

-

Observe and adapt: Monitor which species show stress or dieback on your land.

-

Diversify plantings: Incorporate species or genotypes with higher drought tolerance.

-

Adjust density: Thinning forests may reduce stress on remaining trees by lowering competition for water.

-

Plan for fire: Anticipate more frequent wildfires and manage stands to reduce fuel loads and support recovery.

Extension specialists and Oregon Department of Forestry professionals can help landowners tailor these strategies.

Preparing for Uncertainty

While exact projections vary by emissions pathway, the direction is clear: Oregon will be hotter, drier in summer, and more fire-prone. Winter storms may become more intense, bringing both flooding and erosion risks.

Given this uncertainty, forest managers are encouraged to build flexibility into their strategies, recognizing that the most resilient forests will be those prepared to adapt.

Conclusion

Oregon’s climate is already shifting, with profound implications for forests, rivers, wildlife, and communities. Temperatures are rising, snowpack is shrinking, droughts are lengthening, and wildfires are becoming more frequent.

For landowners and forest managers, the challenge is clear: to act now in ways that give forests the best chance of thriving in an uncertain future. By observing local conditions, diversifying strategies, and preparing for extremes, Oregon’s forests can be managed not only to survive but to remain vital in a warming world.

Leave a Reply